Team dynamics after AI

I gave this talk at Agile Cambridge on 2 October 2025

Thank you very much for having me. I’d like to start with a quote from Ian MacKaye, who is a musician and also a skateboarder:

“Skateboarding is a way of learning how to redefine the world around you. For most people, when they saw a swimming pool, they thought, ‘Let’s take a swim.’ But I thought, ‘Let’s ride it.’ When they saw the curb or a street, they would think about driving on it. I would think about the texture.”

My name is Duncan Brown. My job, since August, is CTO for Digital Prevention Services Portfolio which is a group of roughly 600 people inside NHS England. The NHS is one of the largest organisations in the world, and accordingly difficult to get to know, which is highly relevant for this talk, but I’m here as just me.

Before I joined NHSE I spent just over a year and a half as Head of Software Engineering at the British Government’s Incubator for AI, which was first attached directly to Number 10, and latterly to the Government Digital Service. At i.AI we sought to build AI-powered services from the centre, and also to partner with other Government departments to help with their problems. And before that I worked on a national teacher recruitment programme for the Department for Education. Before that I worked in startups and did various other things.

Now I pitched this talk to Mark [Dalgarno, who runs the conference] early on in the summer. Of course, at the speed of change we’ve seen lately, AI-in-software-development content tends to age quickly and badly. But I’m going to try to give you something of lasting value by talking about people, not machines. Let’s begin.

So much of the discourse around AI assumes an inevitability to

adoption, seeing quality as the only barrier to that. That’s true of

hype-dreams like the AI 2027 document that projects “superintelligence”,

whatever that is, in the next 2 years. It’s also true of the Tony Blair

Institute saying there are £35bn worth of AI savings to realise in the public

sector, and it’s true of any conversation where we speculate about “when” AI can

do something.

So much of the discourse around AI assumes an inevitability to

adoption, seeing quality as the only barrier to that. That’s true of

hype-dreams like the AI 2027 document that projects “superintelligence”,

whatever that is, in the next 2 years. It’s also true of the Tony Blair

Institute saying there are £35bn worth of AI savings to realise in the public

sector, and it’s true of any conversation where we speculate about “when” AI can

do something.

Downstream of inevitability we have the discourse of feasibility, of how we get

it all to work, which tends to treat inevitability as given. I don’t usually

like to share this sort of content [a McKinsey report called “Seizing the

Agentic AI Advantage”], but it’s indicative.

Downstream of inevitability we have the discourse of feasibility, of how we get

it all to work, which tends to treat inevitability as given. I don’t usually

like to share this sort of content [a McKinsey report called “Seizing the

Agentic AI Advantage”], but it’s indicative.

I think we ought to be talking instead about desirability. I’m coming at this from the point of view of having run services for thousands, tens of thousands, and now millions of users.

It seems to me that what we choose to have reflected, magnified, transformed by this magic mirror that is AI reflects, in turn, on us. I am going to argue that irrespective of the merits of our choices (which are often real merits), the use of AI always promotes the legible, the quantifiable, at the cost of the illegible. But as teams and systems scale, the illegible—usually the social and the small-p political—tends to dominate the work.

And there is a cost to this. But there are also benefits, if you look for them. There are things we can now learn about teams and about work thanks to the existence of AI and the questions it invites.

During my time at the Incubator we ran a lot of small teams. Some of them were very small—one or two people, usually AI Engineers. There was a blog post that was widely shared and often referred to around the organisation, especially amongst those smaller teams, but it had a lot of currency at management level too. It was called The Era of the Small Giant. The writer, who’s naturally the founder of an AI startup, writes about “reimagining what exceptional people can accomplish when unburdened by the friction of organizational mass”:

The moments of true breakthrough, of genuine innovation, have almost always come from small teams. Specifically, groups of fewer than 7 people—individuals who are exceptional at their craft and deeply aligned on vision….

Now, imagine taking that small, high-functioning team and amplifying each person’s capabilities tenfold through AI tools. This isn’t hypothetical—it’s happening right now.

I call this emerging reality “The Era of the Small Giant.” Small in headcount but giant in impact.

Amplification is a dial that until recently we didn’t even know we could turn.

And this is extremely emotive, assertive language. “true breakthrough”, “genuine innovation”. And the author follows up with what seemed to me and still does seem to me to be an astonishing further assertion, which is that “amplification” through AI must be a good thing, not just for the individual but for the team itself.

That is a serious claim requiring serious proof, which is not included in the blog post. But this idea clearly has great power, and I think one reason for that is there is a kernel of truth in there: like him, I’ve found that small teams, as long as they’re competent, seem to be better at getting things done. Synchronisation is a lot easier. Nobody has to be someone else’s stakeholder. You can have a good time.

This is what I mean when I talk about the uses to which we put AI reflecting what we ourselves care about. We do truly wish, in our hearts and social souls, for a small team. So the golden hammer has found a nail: you can keep a small team, but instead of doing the I think reasonable, expected thing of breaking up the domain and the team together when things get too big, you just give them bigger levers.

The question I guess this person and their AI startup are inviting us to ask is “now where can I get these levers?”. The question I’m interested in is: what does this mean for the work?

In AI discourse there’s a standard counterargument to posts like that. The counterargument goes that because AI can make artefacts, if you understand much of the work of the team to be making artefacts then making 10 times more artefacts is undeniably good. But artefacts are not really what the work is about. There’s another line to tackle about AI enabling the small team to “have context”, which I’m going to come back to in a minute. And artefacts can be, to put it mildly, extremely useful.

There’s a world view here about what software development actually is, and this feels like the sharp end of a transition that’s been going on for at least as long as I’ve been in the industry. I think it’s easy to forget—or if you’re younger, why would you know—just how antisocial the work of software development was perceived to be around the turn of this century. Certainly the popular perception of the job then was that it was 100% artefact production for nerds. It feels uncanny to me to have that perspective spoken for again.

But I assume most of you attending this conference about Agile are used to the rate of artefact production being amongst the least of your worries in a team of any maturity. And yet… wouldn’t it be nice? Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to create a prototype of that in 20 minutes. Wouldn’t it be nice to just not have to write that module. Wouldn’t it be fun and wouldn’t it above all be pragmatic.

But here we are in the “emerging reality”. And it turns out, and I have observed this, that when you create a lot of prototypes in 25 minutes each, that what you do is create masses of work for everybody else. Your colleagues have to look at it. Your researchers are going to have to talk to people. You’re going to have to work out how to publish and share it. You’re going to have to deal with your boss who saw it and now insists that it be rolled out to tens of thousands of users. Prototypes can indeed be cheap: you could just draw a picture.

I led a project which took full advantage of AI’s production tools, only to run heavily and terminally aground on organisational governance and confused expectations in the department with which we were engaging. In that situation there was literally no quantity of artefacts that would have helped.

Whilst this failure is a little disappointing, it’s interesting to observe that this doesn’t work. It’s signal. We can now say: we live in a world, sorry, an “emerging reality”, where we can have [waves hand] anything at any time to a basic level of competence, and all of the real problems, the “people problems” still exist. And this is finally proof positive, hard evidence, that artefacts are not really what we’re here for. We are demonstrably optimising about a mile from the bottleneck. AI may be giving you a million prototypes, but if you listen, AI is telling you in quite a painful way that being able to get feedback on your artefacts is much, much more important than the artefacts themselves.

And now it’s easier than it’s ever been to make that argument. Good!

So amplification is seductive. The other means of augmentation that AI theoretically offers is hybridisation: two skill sets in one head. And I think this is interesting.

In a mature team I ran a few years ago at the Department for Education, we inaugurated regular, public design-dev catchups to be explicit synchronisation points between disciplines, because ad-hoc communication was too sporadic and tended to take place in private conversations. This worked really well.

The challenge from AI to do that differently sounds a bit crazy when you say it out loud, but I think crazy in an interesting way. Instead of having to set explicit synchronisation points, what if we arranged it so that the people who depend on each other, say me the technical lead, and my colleague Adam, the lead designer, were the same person. There is no faster feedback loop, certainly, than the one inside your own head.

We do want shorter feedback loops and lower synchronisation overheads! So here again is the golden hammer: right now the price we pay for multiple skill sets is that we have to have multiple people, and then we have to keep everyone aligned. AI proposes: let’s tool them up with skills as and when required. Again, we never thought of this because obviously you couldn’t do that. You can’t put two brains in the same head.

Now, maybe, we can. Can we? And more importantly, now we can ask what that means.

To try and answer that question I want to get a bit more concrete and talk about UI design specifically, because the commodification of design through AI is something that was absolutely rife at the Incubator and I believe it’s rife in the world at large. I saw more than one Incubator team ship very functional and often widely-adopted (within niches) products without a single glance from a designer, and I took part in multiple senior conversations where recruiting designers was weighed up directly and explicitly against recruiting engineers, with this kind of issue in mind.

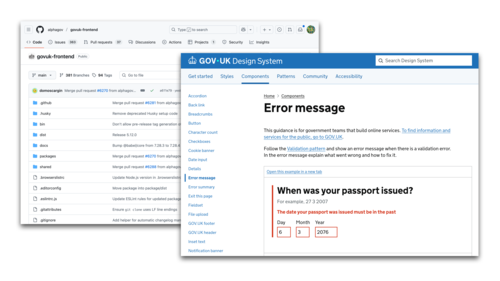

Quick sidebar on what I mean by “design”. For those of you who haven’t worked in public sector contexts, the role of designers in the classic GDS-style multidisciplinary team is quite particular. They work overwhelmingly with existing components that are enshrined in the GOV.UK design system and made available through common tooling. This means their job is not to invent visual aesthetics. It’s all about how it works, not how it looks. Many of them write code and they contribute to the design system and the tooling, and that’s why the design system works so well.

OK, I’m now going to set out the argument for rolling up the designer into the head of an engineer. I think it goes like this:

“In this world where we have a really mature design system, it’s really easy for AI to do a good enough job because the vocabulary exists: everything has a name. Two designers talking about radio buttons, you know exactly what they’re talking about and so do they and so can the AI. If this is true, the AI can think in the same terms as the designer and there’s a finite set of components to choose from, the designer moves from being a necessity on your team to a luxury.”

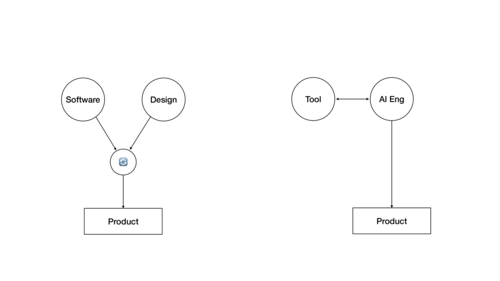

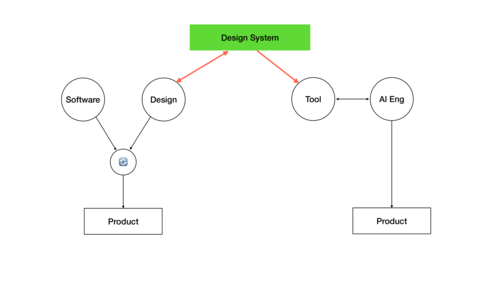

Let’s draw a quick picture of that.

So over here on the left there’s me and there’s Adam, the lead designer. And here in the middle is the conversation we’re having. And the product comes out of the conversation, that co-design. And over here on the right is the “emerging reality”. Over here an AI Engineer interacts with a tool in a very fast feedback loop, and the product flows directly out of their fingertips.

Now I think there’s a flaw in this proposition.

I’ve left something off here. What I have left off is the connection to the design system and the tooling ecosystem that makes it possible for this tool to do this. So let’s stick that on.

Now we see a cost. Adam’s is a read/write relationship and over here is a read-only relationship. Fine if one or two people do it, but in the inevitable tragedy of the commons, this is on the way to being out of date and redundant. Because all the juice that comes from the world, from the engagement with real problems, is getting diluted. Less feedback! As you can imagine, this [the design system] gets weaker, then this [the tool] gets weaker, then this [the product] gets weaker. Even though this person [the AI engineer] continued doing their best throughout.

And the nature of that weakness is that this is all becoming generic. We are taking intention out of the system, we’re taking information out of the system. It’s entropic. Whereas once a new kind of problem would result in feedback, now it’s harder for the system to sense changes in the world and adapt to them, even as it’s used in more and more diverse contexts and might be expected to receive more feedback. It will go stale faster.

I believe I saw this happen. I had expected part of the work of the Incubator to be to contribute back design system patterns around some of the novel things we were doing with the technology, especially around interfaces for human supervision and oversight, some of which were novel and very interesting. But it took a really long time and quite a lot of conversations even to hire a lead designer, and the status of design remained somewhat in question. I don’t think this was necessarily a prejudiced decision. From the org’s perspective it made total sense: we could keep on shipping regardless.

There is one more cost to identify here, perhaps a cousin of that, which is that in a project which fails, or even one which succeeds, the amount of learning, and therefore of cultural change, is multiplied by the number of heads involved. Both Adam and I, not to mention the rest of our team, have gone out into the world with our experiences. In the Incubator project that failed because it was rejected by the organisation, all we could do, the three of us who had tried, was play back our story to the rest of the team for 45 minutes on a Thursday afternoon, and that felt inadequate.

So I want to put the argument against hybridisation in 3 ways.

First I want to make an argument from diversity. The skills and experience, including life experience, each of us has directly shape our understanding of the problems we are trying to solve. Like Ian MacKaye, they look at a swimming pool and they’ll think “let’s ride it”. It’s wrong, but it’s not actually wrong. With those multiple perspectives we solve problems better and more thoroughly because we can develop and challenge each other’s intentions. That requires individuals, it requires niches, and it requires exposure to problems.

So I see the invitation to flatten our niches. And my response is, thank you for reminding us of how important niches are! And let’s take this as a spur to dig them even deeper, and to champion and celebrate teams, and to hire people, that are as diverse as possible.

Second I want to argue that it undermines the skill of translation that is the grease in the machine of multidisciplinary teams. In translating between our disciplines we spar with each other, and we put that into practice when we engage with the wider organisation. I was at a panel yesterday where someone argued that translation was the critical skill for successful digital transformation. It’s a slightly silly question, but it’s a good answer, because transformation is a continual negotiation between worldviews that don’t really understand each other. The echo chamber of your own head will not equip you for the actual work.

Finally, and I think this is very clear-cut, the lifeblood of the tools is their continual freshness, which comes from change in the agreed patterns. Change is driven intentionally, as far as I know, by individuals learning from direct practice. And if you increase the size of the audience and simultaneously reduce the numbers of real practitioners, i.e. the people who drive that change in the ecosystem, you will first see diminishing returns, and then you will kill the ecosystem, and then you will kill the tool.

The design system is only one example here. Another good example would be the Incubator’s Extract project. That project was mostly coded with AI, but it could not exist without the highly-evolved planning data ecosystem that has been intentionally built up over years at planning.data.gov. You could also point to open source software, documentation, standards, etc. Anything that is held in common is now subject to a new kind of attrition, the attrition of casual consumption.

Not because it’s being used more, but because the skills that shaped it and made it viable are devalued because they are not legible.

So much for having skills. What about acquiring them? In this world too, AI optimises for legibility. You can go on LinkedIn today and find any number of articles about seniors getting all the benefit from AI while juniors lose all their learning opportunities and so on, being short-term empowered and long-term disempowered by the tools. And you see increasingly panicked discourse like should grads go directly to train in “architecture” and fun stuff like that because supposedly that’s all that’s going to be left.

For a junior dev, the golden hammer wangs down on “autopilot”, not “copilot”. But we should ask why these people are here in the first place? Is it actually so they can move low-risk tickets across the JIRA board? In which case: great, let’s immediately fire them and replace them with Claude Code. Or is it something different, of which shipping code happens to have become a core supporting component?

These people are hungry. They are in a continuous process of assessing their options for their next career move. Some will be tech leads and maybe go into management. Some will be happy as Individual Contributors forever. Still others will move sideways into other disciplines or even other fields. The feedback they get from their work and their learning helps them to make these decisions in an informed way, and these are the decisions which shape the way their personal/professional scope expands, from their work, to their team, to their organisation, to their field—all the way up to events like the one you’re at right now. The sort of decisions that end up with us being physically together in this room and books being physically published and institutions existing and not existing and so on.

Just as an infinte supply of “instant code” shows us where the bottleneck really lies in the work, when we can aggressively optimise for the speed at which low-risk tickets move across the JIRA board with a junior developer’s name on them, it seems obvious that this take on what it means to be a junior fundamentally misses a lot of what we are asking these people to become as they come to participate in and shape our teams, our orgs and our field. It also seems obvious that a load-bearing part of those systems right now that we haven’t ever questioned is the now “old-fashioned” form of direct practice which brings junior developers into contact with the work, with the tools, and with the domain. To go back to skateboarding: they start off seeing the kerb, but they come to feel the texture.

I don’t know where this goes. It won’t necessarily directly result in worse code, but I think it’s reasonable to be wary of the direction of travel for the work. I’m worried that in thinning down the direct practice, we are interfering with important feedback loops between people and the domain, people and their teams, their peers, and their orgs.

Disincentivising people from becoming skilled makes niches harder to dig and makes diversity harder to achieve. It makes mediocrity. And it can engender, based on conversations I have had, a kind of existential panic at the way they can run and run and still not seem to be going anywhere.

When a system that has grown organically is forced to account for itself in the face of a new, more “productive” system, it is difficult to make a fair comparison. To weigh the benefits of, say, more communication, more failure and more autonomy, against the much more legible benefits of more features shipped.

In Seeing Like A State, James C Scott writes about the ways in which bureaucracies impose mechanistic systems on people and on nature for the purpose of making the world they govern legible and exploitable. The forest is not an ecology, it is so many tonnes of firewood. And the will to exploit the forest enters into a mutually reinforcing cycle with abstraction. Abstractions (firewood for a forest) enable exploitation, exploitation empowers grander abstractions (gridded city layouts replacing medieval streets), and the things that cannot be measured (ecology) are collateral damage.

What Scott describes at the level of monarchs and nations also occurs in the mundane environment of work. Ivory tower software architecture is a pure expression of this. To extend the forest metaphor, you could you call the incredibly, almost infinitely complicated experience of being close to a problem “ecology” and call the things in your boxes and arrows “firewood”.

The ivory tower looms because exercises in generalising always flirt dangerously with cliché, especially when the generaliser lacks context. And yet, AI whispers a promise here too, its most seductive promise, the promise that ought to heal all its other defects: abstractions on tap; just-in-time legibility.

The mediums we use to communicate with each other shape the way we work. Personally I love cheap-to-create public Slack channels; there is an intentionality to those, which is hard to mistake. There is also very low cost of failure if the initiative turns out not to have been viable.

The mediums a team uses are part and parcel of the messages they send. What happens when we try to fillet out the “content” of communications by pulling them out of context and condensing them?

I recently started this job in a large organisation inside another very large organisation. The outer organisation, NHS England, is so large and so complicated that I’ve come to realise, as everyone who works there eventually must that yes, it’s impossible for me to understand it all. I have resigned myself to that.

One of the things I’ve noticed about this organisation, though, and other large orgs, and this was definitely true of the Incubator too in the context of central government, is that we can’t stop giving things names. When things are too big or complicated for the names we give them, we continue to refer to them, but allow the language to lose a lot of meaning.

In this way things that are hard to name resist compression. You keep pulling out the same file from the filing cabinet but the file always has something different in it, like the compressing and labelling process that usually takes place when we name something hasn’t worked.

Everything in my world (“prevention” for example) has dozens of faces and dozens of names, and those names themselves are shared by dozens of further faces of further things. The language is deliciously, hilariously inadequate. In practice what this means is that it’s actually quite difficult for me to read a given situation and make it legible for my purposes, and understand what of it I need to attend to and what matters to me, what risks it presents.

In this environment even my purposes themselves are hard to read. Why am I doing what I’m doing, and could I be doing something different and more useful, in this colossal, dynamic system that I can at best dance with, per Donella Meadows, but cannot possibly master?

For me and for everyone I work with, this information environment manifests in torrents: through our inboxes, through meetings, through Slack and Teams, through pull requests and tickets and memos and commissions and conversations.

For me, the information environment at work resembles nothing so much as the attention economy we all know and hate from outside work, where content jostles for our eyeballs. The drivers when I open my phone are dopamine, social validation. But at work my attention tends to be directed by anxiety, time pressure, and purpose (if I can get it). And there’s one more difference, which is that at work, there are potentially quite serious consequences for missing a beat.

So just as the social algorithms are feeding me content that’s in the neighbourhood of content I seem to like, at work I’m operating my own algorithm, choosing what to permit myself to become invested in. This is how I spend my one wild and precious life. And when I choose to attend I’m dipping my cup into a stream that is very fast-flowing and very deep.

When AI offers us the means to deal with “too much information”, the proposition must be that it will automate that internal “algorithm” that decides what we attend to. Like a mother bird partially digests a worm before regurgitating it into her babies’ mouths, AI can hunt down the valuable information, partially digest it, and regurgitate it into me.

These summaries are automated sense-making, relentlessly compressing the uncompressable.

Somehow people are surprised that getting the AI to be accurate is difficult. But it’s not a technology problem, it’s a philosophy problem. You are trying to satisfy billion-dimensional, ever-changing, utterly subjective, embodied “truth”. And this thing will also supposedly give us all the unbiased view from nowhere. And we will achieve this, supposedly, through “guardrails”? But that just doesn’t make sense.

I hate having so many meetings. I cannot bear the idea that we are sliding inexorably into entropy by way of too many meetings. I’ve seen a lot of evidence in the public sector that we are, and it seems to be getting worse. And frankly I worry that the end of this will not be pretty. Be that as it may, the solution is surely not to reduce the perceived cognitive cost of meetings by making sense of them by an automatic process. When you say it out loud it seems mad. If anything we should be making meetings more painful, not less.

But let’s take the opportunity to ask the useful question. “Even if we could automate this stuff up to the nines and have meetings all day long and never be in danger of losing hold of a salient point, would we want to?” And for me the answer, having peered over the edge of that abyss, is a resounding “no”. No way! I don’t want to live in the faster-and-faster-swirling work attention economy being chaperoned by systems that cannot be surprising. More information, more summaries, more information, more summaries, and more entropy at every crank of the handle. It’s a singularity, yes, but a singularity of busywork.

It’s based on a fundamental misreading of what matters when we work together, and, both forgivably and unforgivably, it’s lazy, not malignant.

But we can use this. We can use it as evidence to help us build a better world. The first step is to know that the busywork singularity exists and is waiting for us.

And the next step is to take up the challenge and ask, seriously, if we do think we need to deal with the problem of too much information, and we can see that compression is ultimately a bust (and that is important news, and we’re now knee-deep in the evidence), what should we do? What in fact is the information environment we seek for ourselves and our teams?

I believe that rather than increase our efforts to manage large amounts of information by adding smaller, fuzzier versions of the same information on top of it, we should focus instead on shrinking flows of information at the source, by stopping things.

Fred Brooks memorably wrote in The Mythical Man-Month that he regretted setting a team of 150 people to work on something because he didn’t want to see them sit idle. That would have been hard to resist, but it is even harder to stop 150 people from doing something they are already doing, and they see as valuable, and from which the organisation has been convinced it will derive benefit.

I have not yet had the privilege of working in an organisation which is good at killing projects. I would be very curious to hear about such a place if it exists. I imagine it would be a pleasure to work there.

Whether AI is compressing or expanding “context”, it clutters the team’s information environment. When it summarises it misses, when it expands it invents. The meaning of things that are in the process of naming, perhaps that are in the process of being pulled apart for naming, must be continually negotiated between us as people.

There is literally no other way to make sense of things.

We’re coming close to the end now, and I’m going to recap.

I hope I’ve put across my view on skills: they are the senses through which we perceive the work and the problem we’re working on, and our practice of those skills directly shapes our perspective. The deepening of this perspective amounts, in time, to expertise, and expertise creates difference. Difference increases the quality of the work.

This all means that I value a strong coupling between skills and individuals, and I don’t see the kind of “Superhuman” AI engineer who can wear every hat having very much purchase beyond the earliest prototyping stage of a project. I think it’s a good idea to walk fast in the opposite direction, diversifying teams and deepening niches.

For those early in their careers, the automatic task completion machine is malignant. It divorces them not only from skills, but from the problem domain altogether, because by stripping their skills it strips their senses.

On “context”, like everyone I am tantalised by the idea that the jungle of information that shapes my daily life at work could be condensed into a tidy slate. I reject this idea because I believe the work of sense-making belongs exclusively to me. The problem is not insufficently condensed information, because the information is not condensable. The problem is an information environment that requires much more aggressive management.

I often think about Alistair Cockburn’s observation that software teams are a production line not of code, but of decisions. And AI tools that “do the work” simply don’t do that bit of the work. They do all the rest, and they stress out and indeed sometimes they burst the bottleneck.

Iain McGilchrist, a British neuroscientist, wrote a book called the Master and his Emissary, about how the two halves of our brains perceive the world. Part of this book sets out his theory that the way that the left-hand side of the brain works—this is the side of the brain that’s really narrowly-focussed, the part that constructs abstractions—has taken a completely dominant role in shaping the world around us. We have these brains. As with James Scott’s bureaucracies, the systems we choose to construct tend to optimise for exploitation and conceptual cleanliness to the detriment of underlying ecologies. The left brain gives us:

a conceptual version… abstracted from the body, no longer dealing with what is concrete, specific, individual, unrepeatable, and constantly changing, but with a disembodied representation of the world, abstracted, central, not particularised in time and place, generally applicable, clear and fixed.

It is the world of legibility, and it’s the world of cliché. It is the view from nowhere that is the longed-for world of AI.

But it speaks to us.

Why wouldn’t it?

Why wouldn’t we dream that there is no limit to the ladder of abstraction that has its roots in the organisation of electrical circuits?

Why wouldn’t we wish for any large system to be composable from building blocks in the same way as the data pipes and caches of a CPU nestle on a die?

Why wouldn’t we want to hope that the actions and activities that make up the tasks and relationships and purposes to which we put our lives could not be expressed using an exact, finite vocabulary?

We yearn for a team that is a logical closed system and yet the team is not a logical closed system.

The team is just people.

Some of them will be programmers.

Some of them will be designers.

All of them, in their way, will be skateboarders.

Thank you very much.